Tuesday, 12 June 2018

We Are Blind to Many of the Reasons for Our Conscious Choices

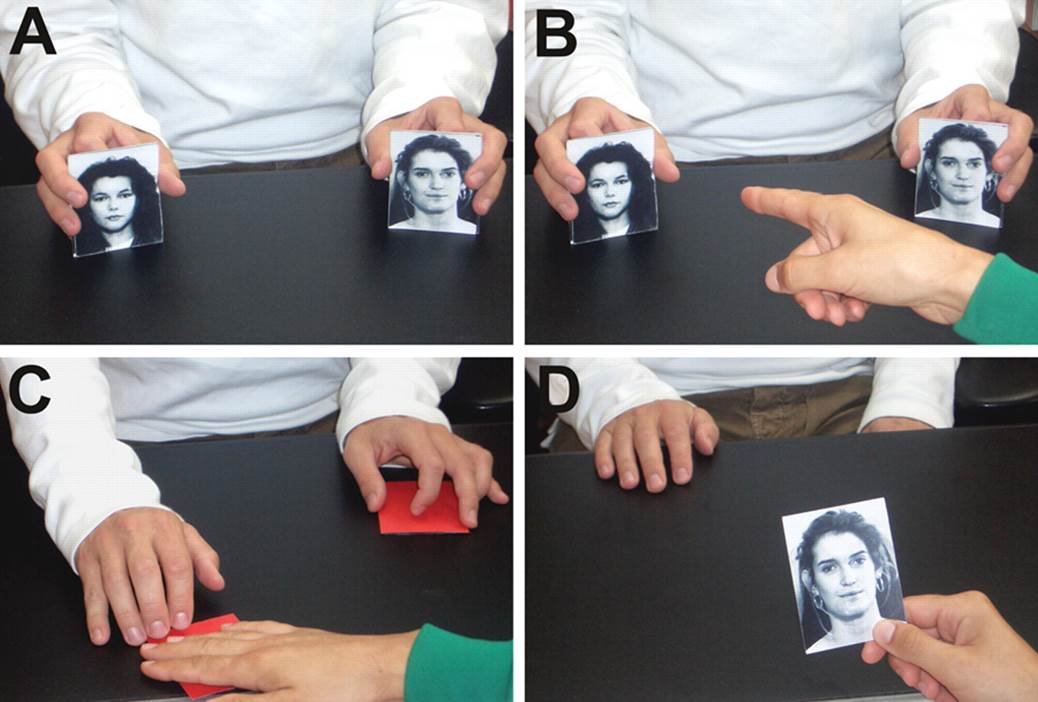

In a study that they conducted in 2005, entitled “Failure to detect mismatches between intention and outcome in a simple decision task”, Lars Hall and Peter Johansson uncovered a spectacular phenomenon. In this experiment, the researchers showed their subjects pairs of cards with pictures of two different people’s faces and asked their subjects to pick whichever of the two people they found more attractive. Once a subject had made this choice, the experimenter took back the cards and then, using a little sleight of hand, gave the subject back the card that he or she had not chosen and asked what it was about the person pictured that made them more attractive. Over 80% of the subjects failed to notice that they had been given the wrong card and actually provided the kind of verbal explanation requested—that it was the expressiveness of the person’s eyes or the overall harmoniousness of their features, or what have you.

Hall and Johansson called this phenomenon choice blindness, by analogy with change blindness, which occurs when someone is so focused on a task that they fail to notice changes in the scene before their eyes. But in the case of choice blindness, we are talking about blindness to our own deepest motivations. This experiment shows that we do not seem to have ready, conscious access to the reasons behind our choices and that we therefore often rationalize them after the fact. These results are reminiscent of Michael Gazzaniga’s famous experiments with people who had split-brain conditions.

In France in 2013, Claire Petitmengin and her team repeated Hall and Johansson’s study and confirmed their findings. But the French team also varied their protocol by introducing, in certain cases, a person who helped the subject to make his or her reasons for choosing one face or the other more explicit. For example, this assistant might say something to the subject like “So now, using this photo of the face that you just chose as being the more attractive, please tell us why it pleases you more.” When prompted in this way, about 80% of the subjects realized that they were being shown the wrong photo. In other words, simply creating a slight doubt in the subject’s mind caused the results to be totally reversed. Petitmengin et al. therefore concluded that although we are usually unaware of our decision-making processes, we might be able to access them through certain kinds of introspection.

From Thought to Language | No comments