Monday, 6 July 2020

Acute stress reaction initiated by a hormone secreted by the bones

Today I’d like to tell you about an article published in the journal Cell Metabolism in September 2019. The article, entitled “Mediation of the Acute Stress Response by the Skeleton”, reports a discovery that is surprising, to say the least. Apparently, all on its own and in just a few minutes, osteocalcin, a hormone produced in our bones, can initiate the physiological changes associated with acute stress, such as increased heart rate, respiratory rate and blood pressure.

Today I’d like to tell you about an article published in the journal Cell Metabolism in September 2019. The article, entitled “Mediation of the Acute Stress Response by the Skeleton”, reports a discovery that is surprising, to say the least. Apparently, all on its own and in just a few minutes, osteocalcin, a hormone produced in our bones, can initiate the physiological changes associated with acute stress, such as increased heart rate, respiratory rate and blood pressure.

Scientists have already known for several decades that such changes are associated with the effect of hormones such as adrenalin that are secreted by our adrenal glands as the result of the secretion of another hormone, ACTH, by the pituitary gland, which is itself stimulated by CRH, a hormone secreted by the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus is a part of the brain that receives signals from other parts when a potential danger has been perceived.

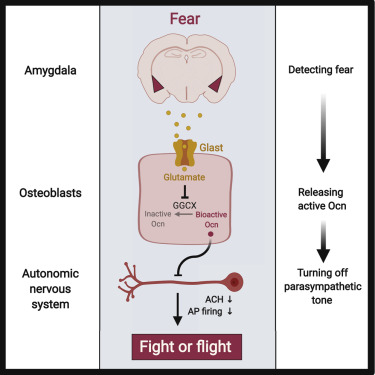

The secretion of osteocalcin appears to be triggered by another part of the brain, the amygdala, that has very close ties to the rest of the body. The amygdala apparently sends out a signal that causes certain bone cells, known as osteoblasts, to release osteocalcin into the bloodstream. The osteocalcin then inhibits the parasympathetic part of the autonomic nervous system (the part that promotes rest and digestion), giving full rein to the opposing part, the sympathetic autonomic nervous system, which is responsible for our fight or flight response to perceived threats. And because the sympathetic nervous system is, so to speak, the front line of the fight or flight response (for example, this system directly innervates the adrenal glands), it is no surprise that by promoting action, osteocalcin has a very rapid effect on the entire body.

From that moment on, a broad spectrum of physiological phenomena are stimulated, including metabolism in general, and even memory (accurately remembering the circumstances under which you were attacked so that you can avoid them in future is highly adaptive). And one strong piece of evidence for this hypothesis is that just like humans who have adrenal insufficiency, rodents whose adrenal glands have been removed still have this typical reaction to acute stress. There must therefore be other pathways that produce this response (this would not be the first time that researchers had found redundancies in the human body’s signalling system). One of the authors of this study, Gerard Karsenty, believes that osteocalcin has been playing this role ever since the first vertebrates with skeletal systems emerged. Thus our bones may not only enable us to move, but also enable us to move faster when we have to. There’s a certain evolutionary logic in this idea.

Body Movement and the Brain | Comments Closed