Tuesday, 13 October 2020

Our perceptions are shaped by the possibility of imminent actions

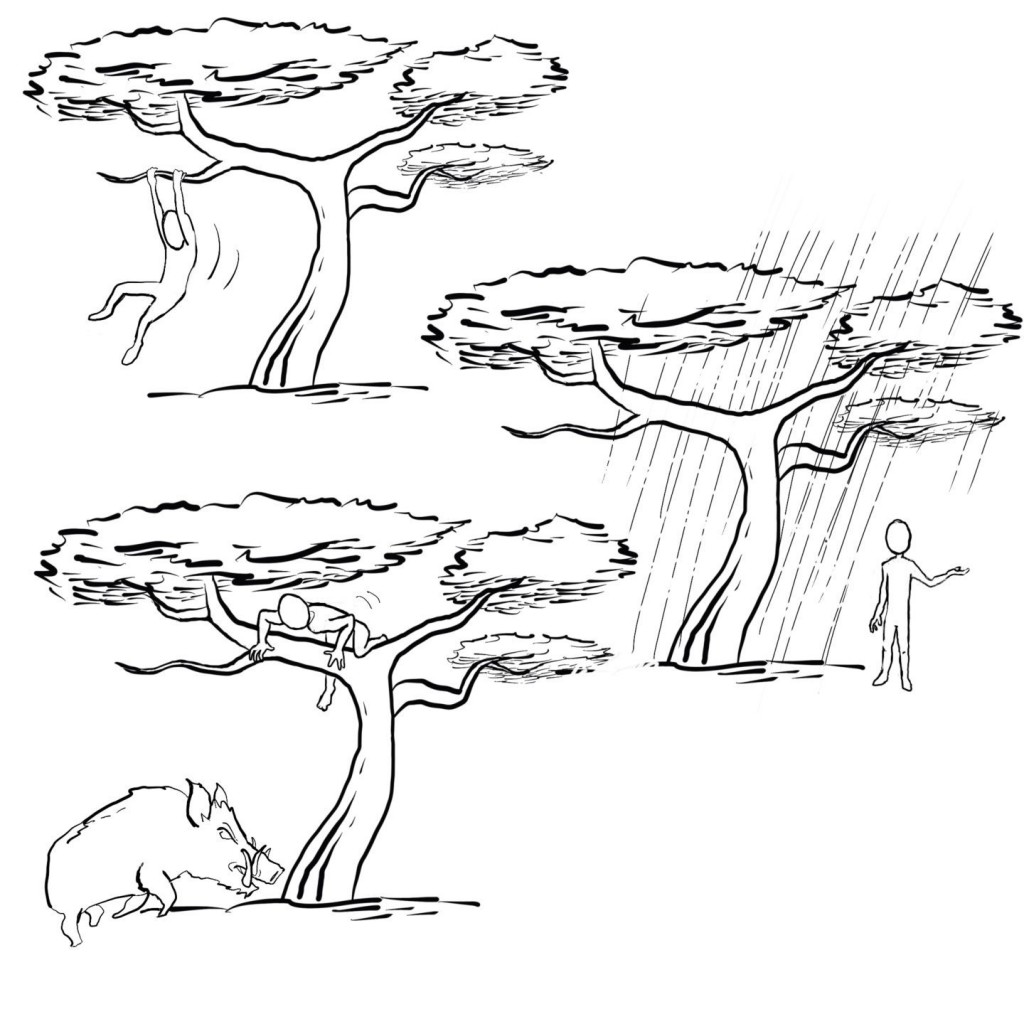

Affordances are a key concept in cognitive science, first advanced by J.J. Gibson in 1966. As I explained in an earlier post in this blog, an affordance is an opportunity that an object offers to take action. A hammer, for example, offers the opportunity to be grasped by its handle, and a chair offers the opportunity to sit down. What is interesting about this concept of affordances is that the opportunity for action does not depend on an object’s characteristics in any absolute sense, but instead is relative: it depends on the possible relationships that a particular organism may establish with that object. A tree, for example, offers different affordances to humans, who may use it as shelter from the rain, or crows, which may use it as a perch, or to woodpeckers, which may use it as a place to hunt for food. Moreover, as the above illustration suggests, any given object (again, such as a tree), may inspire different affordances for a given organism (such as a human) depending on that organism’s motivations and/or the broader general situation.

There is a large body of neuroscientific research, notably including the studies by Paul Cisek and his colleagues, showing that the brain is constantly simulating the actions suggested to it by the affordances that it perceives in its environment. In physical terms, this means that certain populations of neurons begin to increase their activity with a view toward possibly increasing it even further to actually carry out the actions suggested to them by the affordances that their environment suggests to them. These studies showed that certain “pre-motor” areas of the brain were thus activated in our day-to-day perceptions, which therefore operate to identify objects’ affordances much more than their physical characteristics such as size, colour, and shape.

But what about the brain’s sensory regions themselves, such as the primary visual cortex? Surely they can’t be “contaminated” by signals from affordances in the outside world, because that might prevent them from doing their jobs as “objective” sensors of the properties of objects. And yet the brain’s sensory areas, just like its motor areas, are in fact affected by affordances, as was shown by Zakaria Djebbara and his colleagues in a study published in the journal PNAS in July 2019.

In this study, subjects wore virtual-reality headsets, along with electroencephalogram sensors that recorded their brain activity as they performed a task in the virtual reality environment. The task began in a virtual-reality room with a door in one wall, leading to another room. In each trial of the task, the door could be any one of three widths: too narrow to pass through, just wide enough to pass through, and wide enough to pass through easily. When the wall turned red, the subjects didn’t have to do anything. But when the wall turned green, the subjects had to try to walk through the door. The researchers made two very interesting observations. First, the type of neural activity in the subjects’ primary visual cortexes depended on the affordance offered by the door, that is, whether or not the subjects perceived it as passable. But second, and even more interesting, this dependency was observed only when the wall was green—in other words, when the subjects knew that they were going to have to try to pass through the door.

These findings suggest that the subjects actually saw the door differently both according to the affordances (degrees of passability) that it offered and to the situation at hand (whether or not the subjects had to try to pass through the door). In other words, as Gepshtein and Snider might put it, these findings support the ideas that our perceptions are shaped by the possibility of imminent actions.

Body Movement and the Brain | Comments Closed