Monday, 31 December 2012

Speaking Without Broca’s Area

From Dr. Paul Broca’s observations in the 1860s, we know that the left inferior frontal cortex of the brain, now also known as Broca’s area, is heavily involved in human language abilities. At first, this area was thought to be associated only with the production of language, but gradually its role has come to be regarded as more complex, and recent brain-imaging data have actually made the old dichotomy between language-production areas and language-understanding areas somewhat obsolete.

This earlier, more simplistic model has increasingly been replaced with a more dynamic conception of the brain, in which specialized areas are still recognized, but the networks of neurons are regarded as more flexible and capable of being recruited according to the requirements of the task at hand.

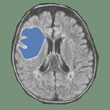

This new, more dynamic model of the brain’s language functions is supported by clinical studies such as the one conducted on patient “FV” by Monique Plaza and her team in 2009. Patient FV had developed a tumour in a relatively large area of the left hemisphere of the brain, including Broca’s area. This tumour was removed surgically.

Plaza and her team assessed the patient’s language abilities before, during, and after the surgery, using standard tests and some other, more specific ones. The patient displayed the deficits that are typical immediately after surgery, but then regained most language functions. This phenomenon that would be hard to explain using the more traditional localization models. But because the tumour had developed slowly, the researchers believed that some areas adjacent to patient FV’s Broca’s area (such as the premotor cortex and the head of the caudate nucleus) had had enough time to take over the functions of the areas that the tumour had gradually destroyed.

Although tests showed that patient FV still had some subtle language deficits, indicating that this compensatory plasticity was not perfect (for example, the inability to report what someone else had said), Plaza’s findings nevertheless confirmed the usefulness of a less rigid, more dynamic, connectionist conception of the brain.

![]() Speaking without Broca’s area

Speaking without Broca’s area

![]() Speaking without Broca’s area after tumor resection

Speaking without Broca’s area after tumor resection

![]() Contrasting acute and slow-growing lesions: a new door to brain plasticity

Contrasting acute and slow-growing lesions: a new door to brain plasticity

From Thought to Language | Comments Closed