Tuesday, 1 June 2021

Quiz about memory

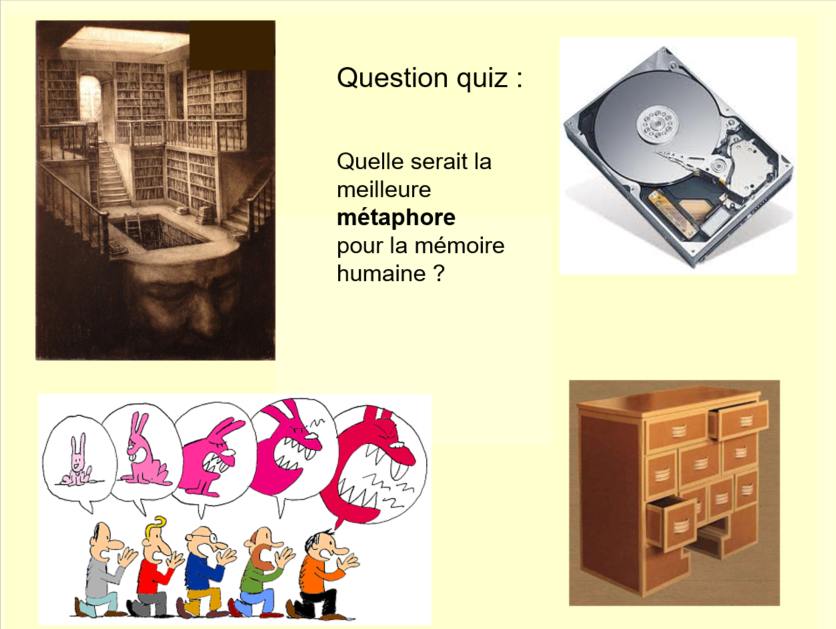

Which of the following is your memory most like: 1) a huge library where all your memories are shelved? 2) a computer hard drive where data are stored in a binary code of 0s and 1s? 3) a dresser with lots of drawers full of memories? 4) the game of telephone, where one person whispers a message to the next until it ends up being distorted?

Which of the following is your memory most like: 1) a huge library where all your memories are shelved? 2) a computer hard drive where data are stored in a binary code of 0s and 1s? 3) a dresser with lots of drawers full of memories? 4) the game of telephone, where one person whispers a message to the next until it ends up being distorted?

Regular readers of this blog will have quickly discarded the computer analogy, whose limitations I have shown many times (although nothing is ever that simple). And I’m always surprised to see that however much I may explain synaptic plasticity to people before asking them this question, they are still often inclined to see their memories as something stored on library shelves or in dresser drawers. Because strange as it may seem at first, the best of these four analogies is the telephone game.

None of the three other analogies is accurate, because all of them assume that we can find our memories stored exactly as we encoded them somewhere in our brains, and that’s not how memory really works. When neural activity reactivates an assembly of neurons that corresponds to a memory, chances are very good that it will no longer be exactly the same set of neurons, because their plasticity or their likely involvement in other engrams will have modified them in the meantime. That’s why we say that whenever you remember something, it is necessarily a reconstruction. Or a reactivation of an engram that is no longer exactly the same as when it was first formed—just like a sentence that has been distorted as 10 or 20 people whispered it to each other in a game of telephone.

Of course, there are some memories that don’t change over time, such as the fact that you were born, or that 2 + 2 = 4 (although that may depend on the creativity of some accountants). But it’s just like in the telephone game: if people are repeating just a simple word, it’s unlikely to get distorted. But research done by U.S. psychologist Elizabeth Loftus in the mid-1970s showed just how malleable our memories are. In particular, she showed that simple suggestions can be enough to get people to change their memories or create entirely new ones. In one experiment, she showed people a photo of a traffic accident, then put it away and asked them to name the colour of the van in the background of the accident scene. Many of her respondents felt certain that they remembered the van’s being one colour or another, whereas in fact there was no van in the photo at all!

These kinds of experiments about false memories clearly show that when you remember an event that is the least bit complex, what you are doing is nothing like playing back a recording exactly as you stored it somewhere in your brain some time in the past. It’s much more like reconstructing something, or creating something brand new, using clues and emotions and influenced by the context or suggestions of the present moment. This also helps to explain why hints, by reactivating neighbouring engrams, can help you retrieve something that is “on the tip of your tongue”.

Memory and the Brain | Comments Closed