Friday, 13 November 2020

Serious problems in the reproducibility of brain imaging results

As I’ve pointed out in previous posts, the results produced by brain-imaging technologies such as fMRI are subject to at least two limitations. First. they detect neural activation only indirectly, by monitoring blood flows in the brain. Second, the methods used to analyze such images are subject to many forms of bias. These limitations were confirmed in a troubling study by Tom Schonberg, Thomas Nichols and Russell Poldrack, entitled “Variability in the analysis of a single neuroimaging data set by many teams ”, published in the May 20, 2020 issue of the journal Nature.

This important study was summarized in another article, in the journal The Scientist. As this article describes, Schonberg and his colleagues asked 70 independent research teams to analyze the same set of data collected in an experiment using fMRI. In the end, the study found, no two teams chose the same approach to analyze these data, and their conclusions were highly variable.

The study’s authors had no difficulty in recruiting 70 research teams to participate. The field of brain imaging, like the field of psychology, has for many years been facing a crisis regarding the reproducibility of its findings. As is well known, being able to obtain the same results when another term of researchers applies the same protocol is a basic principle of the scientific method. But the topics examined in psychological studies and brain-imaging studies are becoming more and more complex, so that the data are becoming less and less clear. Hence researchers must apply all sorts of methods to, for example, increase the clarity of the signal relative to the background noise or to correct errors due to head movements by the subjects of brain scans. Also, they must calculate statistics that apply the concept of a threshold above which the results may be regarded as statistically significant. A huge variety of statistical methods are available, and for various reasons, most of the 70 research teams did not choose the same one.

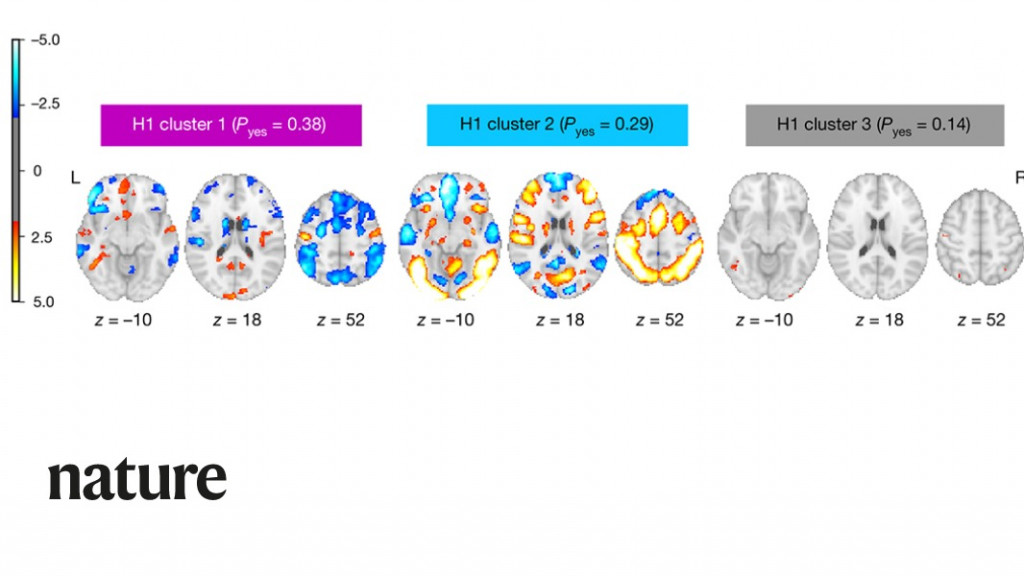

As the authors of the study themselves admit, all of this led to results that were fairly discouraging in terms of uniformity. And yet the task that the 108 subjects were asked to perform in the original study that produced the data was fairly simple. While undergoing an fMRI scan, they had to decide whether or not to bet a certain amount of money. The 70 research teams were supposed to test nine hypotheses about the increase or decrease in neural activity that occurred in various parts of the brain when the subjects made their decisions. On some of these hypotheses, there was broad consensus. For example, the hypothesis that activity in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex would decrease when the subjects lost money was confirmed by 84% of the teams, and three other hypotheses were rejected by over 90% of them.

But for the five other hypotheses, the team’s conclusions showed a great deal of variability. This variability confirmed what many researchers in this field had feared: there were simply too many degrees of freedom in the choice of analytical methods available to them. And to correct this huge problem, the scientific community will have to make several changes. First, for full transparency, researchers will have to provide the smallest details of the choices made in their data analyses. Researchers should also be required to record their hypotheses in advance, so that they cannot adjust them subsequently to fit the data (a practice known as sharking). Lastly, researchers should always try to analyze their data with multiple methods of statistical analysis and a variety of parameters. Such constraints may be burdensome, but they are the only way to prevent the current anomalies and will make it easier to separate real, robust effects in brain-imaging experiments from effects that are mere artifacts of the analytical methods chosen.

From the Simple to the Complex, From Thought to Language | Comments Closed