Tuesday, 9 March 2021

Two very different approaches to identify functional connections between brain areas

Two recent studies have shown yet again that many more different parts of the brain are often involved in a given mental phenomenon than was once believed. In the brain, nothing is really isolated, and there are no “centres” of anything. Instead, we’re always dealing with multiple interconnected areas of the brain that form networks as demanded by the situations faced or the tasks to be performed. What’s most interesting about these two particular studies is that the researchers used two very different approaches to identify functional connections between brain areas: in one study, they visually traced the path of the axons projected by certain neurons, while in the other, they used genetic methods to isolate a new kind of membrane receptor.

Two recent studies have shown yet again that many more different parts of the brain are often involved in a given mental phenomenon than was once believed. In the brain, nothing is really isolated, and there are no “centres” of anything. Instead, we’re always dealing with multiple interconnected areas of the brain that form networks as demanded by the situations faced or the tasks to be performed. What’s most interesting about these two particular studies is that the researchers used two very different approaches to identify functional connections between brain areas: in one study, they visually traced the path of the axons projected by certain neurons, while in the other, they used genetic methods to isolate a new kind of membrane receptor.

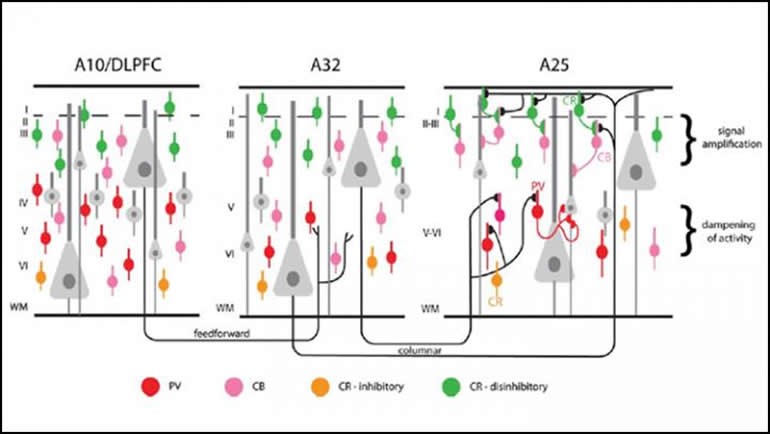

The first study, “Serial Prefrontal Pathways Are Positioned To Balance Cognition and Emotion in Primates”, by Mary Kate P. Joyce et al., was published in the Journal of Neuroscience in September 2020 . Joyce started from the observation that the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is activated by cognitive tasks, while the ventromedial subgenual cingulate area (also know Brodmann area 25) is more active when emotions are being expressed. To ensure the healthy regulation of emotions in response to life’s ups and downs, areas such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex must be able to communicate with areas such as area 25. The problem is that there are very few direct neural pathways between them. Joyce and her team hypothesized that some other area was serving as an intermediate between them.

The researchers were able to confirm this hypothesis by using dyes to mark axons in brain circuits of rhesus monkeys. This marking method showed that some neurons of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex sent axons to the deep layers of Brodmann area 32 (also known as the pregenual anterior cingulate area), where there are large populations of inhibitory neurons. From area 32, other neurons in turn sent axons to Brodmann area 25. Thus we can see how this circuit theoretically has everything needed to constitute an effective network for regulating emotions. This network might lose some of its effectiveness in people living with depression, for example (the study presents some evidence for this, associated with a high density of NMDA receptors in area 25 that are the target of certain antidepressants).

The second study that I want to tell you about is “A Thalamic Orphan Receptor Drives Variability in Short-Term Memory”, by Priya Rajasethupathy et al. It was published in the journal Cell in October 2020. The oversimplistic assumption that this study dispelled was that the brain function known as working memory can be attributed to persistent neural activity in the prefrontal cortex alone. (Working memory is what you use to store information briefly while preparing to provide a response—for example, when you are waiting for someone else to finish talking to you so that you can give them your reply. This ability to retain a piece of information fairly effortlessly for a few moments is helpful in almost all of our day-to-day activities.)

In this study, mice served as the animal model. Since the researchers could not ask them to demonstrate their working memory by reciting a grocery list, for example, each mouse was instead allowed to run a maze several times in a row, while the researchers watched to see which of the possible paths it would explore. Those mice that had the best working memory tended to remember which paths they had already gone down and instead explored others in subsequent trials.

I won’t go into the details of the genetic methods used in this study, but suffice it to say that the researchers were able to identify, on chromosome 5 of the mice, a gene that explained a substantial portion (about 17%) of the variance among the mice that had good working memories and those that did not. This gene, which also exists in humans, encodes a kind of membrane receptor that is referred to as an “orphan” because scientists have not yet determined what molecule binds to it. But one surprising thing that this study did show is that receptors of this kind are found not in the prefrontal cortex, but in the thalamus. The researchers made electrophysiological recordings which showed that these receptors help to synchronize neural activity between the prefrontal cortex and the thalamus during tasks involving working memory, and that the better that mice succeeded at a task requiring their working memory, the greater the degree of this synchronization.

Once again, a mental faculty (in this case working memory) turned out not to be confined to a single area of the brain, but rather to involve the synchronized activity of at least two very different areas. It’s just one step further to say that human beings aren’t made to be confined to a single location and must interact in a wider social network to develop fully. But that would be a bit too close for comfort under the circumstances we’re all living in, so I’ll just say stay safe, everybody, and hang in there!

Emotions and the Brain, Memory and the Brain | Comments Closed