Monday, 20 June 2022

Rediscovery of the traces of another hominin species from the same time as Lucy

The earliest traces of bipedalism are associated with Australopithecus afarensis, the species of the famous fossil Lucy. But if a study published recently in the journal Nature is accurate, scientists have just authenticated different traces of another bipedal species that lived at exactly the same time.

The earliest traces of bipedalism are associated with Australopithecus afarensis, the species of the famous fossil Lucy. But if a study published recently in the journal Nature is accurate, scientists have just authenticated different traces of another bipedal species that lived at exactly the same time.

The human lineage separated from that of the chimpanzees—our closest cousins—at least 7 million years ago. The most notable trait of the Hominina (our lineage) is bipedalism. There is some indirect evidence that the oldest representatives of our lineage were able to walk upright for at least short distances. But the oldest direct evidence goes back some 3.66 million years. That is the age of the hardened volcanic ash at Laetoli site G, in Tanzania, where Mary Leakey and Richard L. Hay discovered, in 1978, the footprints of a hominin who had walked upright.

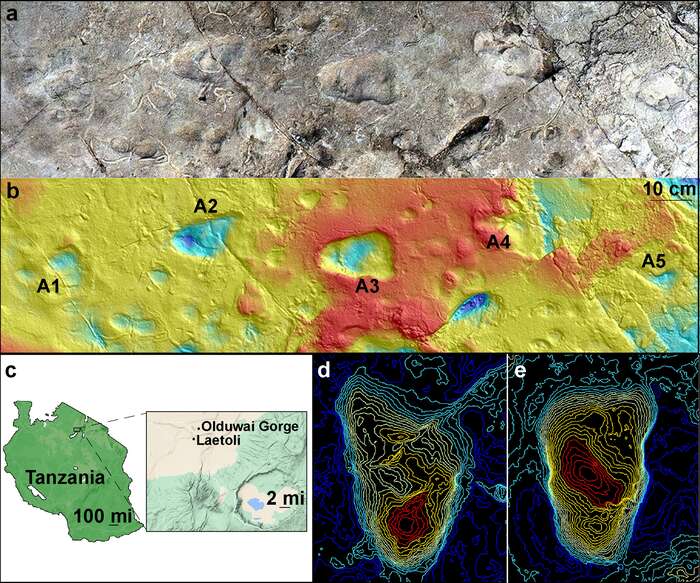

Two years earlier, in 1976, the pair had discovered another site nearby (Laetoli site A) that was especially rich in all kinds of animal prints: about 18,000 in all, of which five seemed to be those of an animal that had walked upright (left-hand photo above). But to many paleontologists, these wider prints and their spacing suggested an animal from the bear family instead. When the far more convincing prints were discovered at Laetoli site G in 1978 (right-hand photo above), people forgot all about those discovered at site A.

That is, until the team of Ellison J. McNutt re-examined them recently using more modern methods, such as 3D scanning (colour image below) and compared them carefully with similarly sized footprints of a species of bear that is alive today.

The study by McNutt and his team, published in December 2021 and entitled Footprint evidence of early hominin locomotor diversity at Laetoli, Tanzania leaves no doubt about their nature: these footprints do in fact seem to come from another species of hominin, different from the one whose prints were discovered in 1978. This means that there would have been at least two species of hominins that were alive at this same time and that may have had contact with each other, somewhat like Homo sapiens and Homo neandertalis were to do much later on.

There is general consensus that the advent of bipedalism in the course of the evolution of our lineage was one of the important factors that subsequently enabled the volume of the human brain to increase. If McNutt’s conclusions are correct, it seems that several species of hominids had this starting advantage at the same time.

Evolution and the Brain | Comments Closed