Thursday, 18 April 2019

Online Game Advances Neuroscientific Research

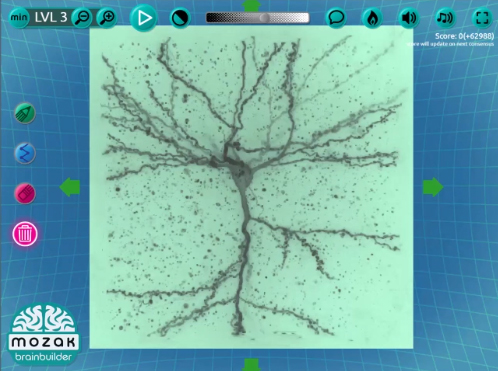

Five years ago, I wrote a post in this blog about a website called EyeWire, on which Dr. Sebastian Seung and his laboratory enlisted the help of the general public to colour the extensions (axons and dendrites) of neurons on various thin, sequential slices of nerve tissue. The lab then used the results to reconstruct each neuron in 3D on a computer. Today I want to tell you about the Mozak project, which has the same objective of reconstructing neurons in 3D. But where Dr. Seung’s EyeWire project dealt only with ganglion neurons in the retinas of mice, the Mozak project deals with neurons from various parts of the brains of various animals. (more…)

Five years ago, I wrote a post in this blog about a website called EyeWire, on which Dr. Sebastian Seung and his laboratory enlisted the help of the general public to colour the extensions (axons and dendrites) of neurons on various thin, sequential slices of nerve tissue. The lab then used the results to reconstruct each neuron in 3D on a computer. Today I want to tell you about the Mozak project, which has the same objective of reconstructing neurons in 3D. But where Dr. Seung’s EyeWire project dealt only with ganglion neurons in the retinas of mice, the Mozak project deals with neurons from various parts of the brains of various animals. (more…)

From the Simple to the Complex | No comments

Tuesday, 19 March 2019

A neuroscientist gets drunk to explain alcohol’s effects on the brain

And that’s not all she does! She also explains the effects of sugar on the body/brain by eating candy, the effects of insomnia by staying up all night, the effects of the flu when she has it herself and even the effects of a break-up by showing how she responds when her boyfriend breaks up with her (or at least that’s what she lets you believe).

The neuroscientist’s name is Shannon Odell, and at the time this blog post was written, she was a neuroscience Ph.D. candidate at the Weill Cornell Medical College of Cornell University, in New York City. In November 2017, she began producing and starring in a series of 5-minute videos called Your Brain On (Blank), in which she explains very entertainingly and accessibly, but with great scientific rigour, just what happens in your brain and your body when you engage in various kinds of behaviours. (more…)

Pleasure and Pain | No comments

Tuesday, 26 February 2019

A Podcast on the Nature of the Human Mind

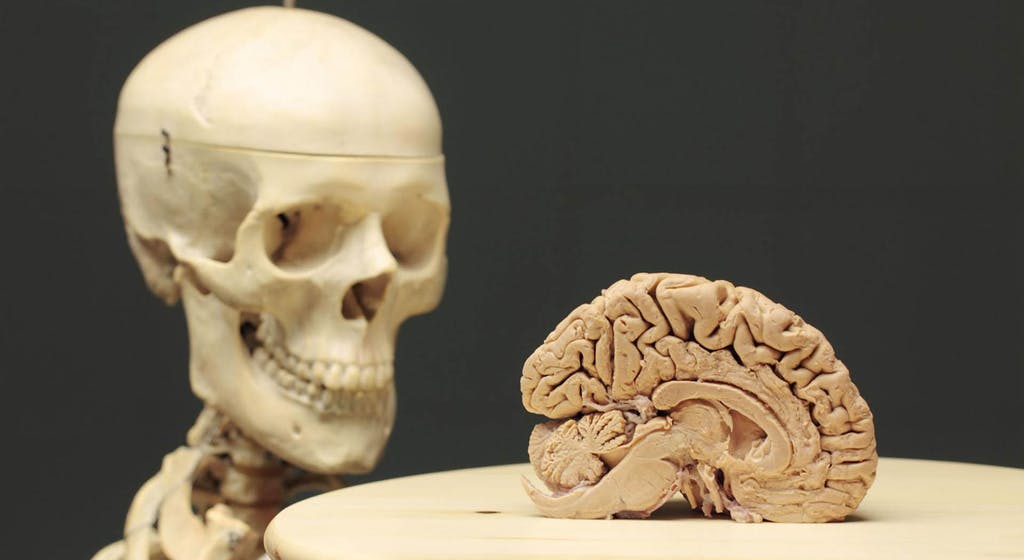

Some of you may be aware of the distinction, in Cartesian radical dualism, between the extended thing and the thinking thing, otherwise known as the body and the mind. A similar but perhaps more insidious distinction is made between the brain and the rest of the body. Likewise, the distinction between the individual and the rest of his or her environment is still taken as self-evident. In all three cases, tradition and “basic common sense” naturally lead us to think of the two terms in each dichotomy as clearly separate things. But in all three cases, according to today’s cognitive science, we are quite simply wrong.

In the June 2018 episode of the podcast Brain Science, Ginger Campbell talks with Alan Jasanoff about his book The Biological Mind: How Brain, Body, and Environment Collaborate to Make Us Who We Are. Jasanoff takes issue with what he describes as a certain “mystique of the brain”—our tendency to overemphasize the brain as a “subject”, as it it had its own life disconnected from the organism in which it is housed. Jasanoff reminds us that, on the contrary, the brain is part of this body that is subject to the biological imperative to stay alive, to postpone for as long as possible the victory of entropy, the second law of thermodynamics—in short, death. (more…)

From the Simple to the Complex | No comments

Thursday, 14 February 2019

A Summer School on Animal Sentience and Cognition

“Without consciousness the mind-body problem would be much less interesting. With consciousness it seems hopeless.” – Thomas Nagel

“What is it like to be a bat?” is the somewhat disconcerting title of philosopher Thomas Nagel’s famous 1974 article on the ineffability of subjective consciousness. In reality, we humans will never know what it is like to use echolocation to navigate as we fly through the air, because, unlike bats, we simply don’t have the bodies or the nervous systems to do so. But the question of animals’ experience in general is nevertheless highly relevant, if only because our human species has the faculty of language and has developed a scientific method that lets us make observations and deductions about the mental states of other human beings and other animals. And because humans domesticate, exploit and exterminate thousands of other animal species, knowing what they may experience becomes an ethical imperative to guide the way we treat them. (more…)

The Emergence of Consciousness | No comments

Tuesday, 22 January 2019

Are Nationalist Sentiments Inversely Proportional to Cognitive Flexibility?

Many studies have shown how certain emotional characteristics can have higher-level cognitive effects. including an impact on people’s political choices. For example, studies have shown that being more sensitive to disgusting things is correlated with having a more conservative political or ethical outlook. Being afraid of nature or even of hearing someone read horror stories out loud is also likely to attract people to the conservative end of the political spectrum. More recently, the opposite phenomenon has even been demonstrated: making people feel invincible through a simple thought experiment can move them toward the more liberal, progressive end of this spectrum. (more…)

Many studies have shown how certain emotional characteristics can have higher-level cognitive effects. including an impact on people’s political choices. For example, studies have shown that being more sensitive to disgusting things is correlated with having a more conservative political or ethical outlook. Being afraid of nature or even of hearing someone read horror stories out loud is also likely to attract people to the conservative end of the political spectrum. More recently, the opposite phenomenon has even been demonstrated: making people feel invincible through a simple thought experiment can move them toward the more liberal, progressive end of this spectrum. (more…)

Emotions and the Brain | No comments